Vivien Leigh

Small World interview

The following is a transcript of an interview with two immensely important Hollywood figures: Vivien Leigh and Samuel Goldwyn. A film critic Ken Tynan is also interviewed, which is rarely seen with men of his profession - usually they're the ones asking questions.

Edward R. Murrow conducted the interview in 1958 for a talk show called Small World. The show mostly covered politics, but other kinds of influential figures also sometimes took the spotlight, which this interview proves. Murrow's role was more than just that of a host - he co-produced all 57 episodes.

In this episode, he is far from action, only occasionally forming a question (and providing an awkward and missed finish to the episode). Interviewees have opinions at times so different from the rest that they frequently square off against each other in heated, but still mannerly arguments.

Vivien Lee comes out as a star of the show, defending her point of view first against Tynan and later against Goldwyn, while remaining friendly and classy. Samuel proves to be a slightly stubborn man holding a controversial point of view regarding Welles' abilities, while Tynan makes a bad impression, presenting himself as a typical critical buffoon, busy with trying to sound intelligent while not making a single quality point throughout the whole interview. He also seems very stressed.

The fact that Goldwyn and Leigh met in one show (albeit in different locations) is reason enough to be interested in this episode. The unique format, occasional changing of roles (who interviews who?) and interesting subjects raise its value even further.

Interview

Sam: This is Sam Goldwyn

in Hollywood.

Vivien: This is Vivien Leigh

in London.

Ken: This is Ken Tynan

in New York.

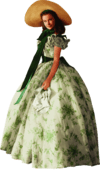

Ed: This is "Small World" and this is Ed Murrow in New York. Good evening! Tonight on "Small World", the world of motion pictures. From London, one of the greatest actresses of our time, Vivien Leigh-Olivier. Miss Leigh won an Oscar in 1938 for her Scarlett O’Hara, another one in 1951 for "A Streetcar Named Desire", and all kinds of awards for her stage portrayal of Cleopatra. Miss Leigh is talking to us from her apartment in London. Good evening, grandma!

Vivien: Good evening, and thank you!

Ed: And from Hollywood, a man who had to get up at 5 o’clock in the morning in order to be with Miss Leigh, Mr. Samuel Goldwyn. A pioneer and a giant, who gave us "Dodsworth", "Wuthering Heights", "Best Years of Our Lives" but whose greatest picture is always the next, which in this case is "Porgy and Bess". And from New York, a young Englishman who, if not angry , is at least opinionated, Kenneth Tynan. Drama critic of the London Observer, now on loan to the New Yorker magazine for a one-year hit. Mr. Tynan, I think I should warn you that Mr. Goldwyn is not always enthusiastic about the critiques that appear in The New Yorker.

Sam: I have great respect for The New Yorker. I think it’s one of the fine magazine that’s come out in my time. But I do not quite agree with the criticism that The New Yorker’s writing. As a matter of fact, I heard about your review yesterday in The New Yorker of the Rodgers and Hammerstein’s show. A Japanese girl playing a Chinese girl - you took and exception to that. Well, the only since we talk about Miss Leigh I always like to talk about her anyway. She played a southern belle in two pictures she was in! And that was... uhhh, what was the name of the first play she gave that great performance? And she won a... It was a picture Selznick did with her, "Gone With the Wind"...

Vivien: Something like "Gone with the Something"...

Sam: ...and she won an Oscar. She distinguished herself again, when she played... which she did a wonderful job in "A streetcar Named Desire". Also a southern belle! I always refer to her as a 'belle' anyway. And tell me, how do you account for your criticism for Chine... Japanese girls playing Chinese girls or Chinese girls playing Japanese girls? What has that got to do with it?

Ken: Well, I think if you’re going to present the other Chinese people authentically, as they ought to be presented on a stage, you’ve got to pay some kind of respect to their, their origins and their culture, their appearance and, and get a kind of authenticity that, I felt, didn’t exist in that show because they are differences of background and temperament between Chinese...

Vivien: But Ken!

Ken: ... and Japanese which are tremendously marked.

Vivien: Ken, you might as well say, that no English actors should play in a Chekhov play, or an Ibsen play.

Ken: If the entire cast is English or, uhmmm, German, ok.

Vivien: But what does it matter if they’re artists, hmm? But does it matter very much if they, if they know what they’re doing?

Ken: Uhm, atmosphere is completely destroyed by this sort of lack of homogeneity, you know.

Vivien: By the way, you know I was the only English member of the cast of "Streetcar" and, so, and that didn’t seem to make very much difference...

Ken: Well, it did to me, honestly dear, because of that... I mean, an entirely English cast - splendid. But you did, at least to an untrained ear such as mine, stick out a little bit as being not quite in the same style as the other people in the film.

Vivien: Well, I’ll have to try again get better. That’s all!

Sam: Mr. Tynan...

Ken: Mhmm?

Sam: ...whom I have great respect for. How is it that about three hundred million people all over the world saw "Gone With The Wind"...

Ken: Wonderful film!

Sam: ...and she received Oscars all around the place...

Ken: Wonderful film, Mr. Goldwyn!

Sam: How is it that they liked her in the role?

Ken: Oh, I don’t think, I was intending that, Mr. Goldwyn, I was saying...

Sam: How is that?

Ken: ...in a film of that kind I think she was marvelous and I thought Vivien was absolutely perfect in that because, as I said, it’s sort of set in the past in a costume picture, uhm, I think that kind of thing is absolutely ok.

Vivien: I think truth is the keynote of all acting or of all artists. And I don’t really understand what Ken’s saying because I don’t think you would call it a stylized film In any way. It’s not like an 18th century comedy, for instance. It was a perfectly human story, and as modern as they come, really. The fact that you wear a costume doesn’t make any difference to your mind. And if you’re mind is truthfully playing the character you’re supposed to be playing, the costumes or whether you have, a fan in your hand or anything, it doesn’t make any difference at all.

Ken: Isn’t there something, though, in those two parts, Vivien, the "Streetcar" part and the Scarlett O’Hara one, didn’t they both have this strange quality of vulnerableness? You know, girls who were easily breakable, who were, who were, uhm, suffering terribly...

Vivien: I think...

Ken: ...and...

Vivien: Sorry Ken, they were entirely different people.

Ken: But, I...

Vivien: It seems to me.

Ken: But didn’t they have that in common? These were girls that were going to be, you know, knocked around by, by all kinds of agonies and, uhm...

Vivien: Oh, knocked around is one thing! I think they were both knocked around quite a bit, but one overcame the knocking around and the other one succumbed.

Ken: Yes.

Vivien: And therefore they were innately different. It seemed to me. But then the only interesting thing, I think, is to play as many different things as possible. I think type-casting and type-acting is one of the menaces, really, because you get used to what somebody’s going to do and then it holds no surprise for you. And if you’re not going to be surprised in life, uhm, it’s a pity, I think.

Ken: Why do you think you get cast so often as, uhm, southern belles, Vivien?

Vivien: I can’t imagine! I must have lived there in some incarnation or other, or something, you know. I really don’t know. Only twice, you know. Only twice in, oh, how many years? Twenty? So that’s not many.

Ed: Miss Leigh mentioned typecasting, which of course is a product of the star system. And I suppose one reason that she has not been typed is the fact that she is a genuine actress, as well as a star.

Ken: Isn’t a definition of the star, though, Vivien, a girl who can stare into a camera and convince every man out there that she needs him, and cannot exist without him?

Vivien: Well, now I don’t think it applies entirely. She may think she wants to say that, uhm, to everybody, men, women and children . I don’t think men are all that important.

Ken: But I mean isn’t there a special kind of hungering, yearning, needing expression which Garbo had, which Marlene Dietrich has and I also think you have it. This sort of look of unutterable need, and everybody in the audience feels "My goodness, she needs me!". I...

Vivien: My goodness, Ken! I think that a certain waif like if you like not, I don’t mean waif like but I’d think people shouldn’t appear too sure of themselves because they probably aren’t, as a rule. Is that what you mean?

Ken: Yes, but I mean is there anything else which, uhm, differentiates star quality from ordinary, uhm, competence?

Vivien: I, I haven’t the faintest idea. I only know that a star to me is somebody who makes me feel that I don’t understand quite what they’re doing, but I feel there’s a sort of magic about it. I don’t know what it is. Garbo certainly had it and, to me, Brigitte Bardot has it.

Ed: Now Sam, Ken Tynan started a considerable controversy in Europe, when he said that the drama as an art form had to be concerned about politics. How do you feel about that?

Sam: How do I feel about it?

Ed: Yes.

Sam: I think the duty of the producer is to produce plays or pictures that the public will enjoy when they’ll go into the theatre. I think politics is a documentary problem. I do believe this that when you leave the theatre you have to carry away something with you that is close to people’s hearts, that touches on their daily life. And they understand the characters. But I do not agree with Mr. Tynan at all about politics. Every time anyone has tried to do that in a public pictures or plays, they usually came out so that they couldn’t pay their payrolls every week.

Ken: Can I comment on that, Ed?

Ed: Please do.

Ken: When I say that art ought to be in some way a political activity, what I mean is that it can’t help it. Every act that anybody performs has some kind of a, uhm, political repercussion.

And, any film, whether it’s that a trivial comedy or a historic epic, is in some way connected with the political activity of that country. Now, if you make a film, for instance in which a negroes are presented not as a different kind of person, but just an ordinary person like everybody else, that is a social act, and it will have all kinds of political repercussions. Now, in a film like "Gone With The Wind", the aristocratic Old South is the subject. Certain aspects of it were omitted, others emphasized. And in those emphasis, in those omissions, politics express themselves. Politics are how we organize ourselves in every form of expression, in every art, every word we utter in some way contributes to the political scene. You can’t keep it out of it.

Sam: Mr. Tynan, when I got the idea of doing "The Best Years of Your Lives”, what I understand you liked...

Ken: Yes, tremendously.

Sam:... I did not think of politics. I only thought of what’s going to happen to these people when they’re returning from the war. The disabled veterans, and so on and so forth. I never injected politics in it.

Ken: But it did explain to you how American society worked. And that was a tremendously important thing.

Ed: Miss Leigh, do you think movies or, for that matter, theatres ought to have a point of view?

Vivien: I do.

Sam: But this had a point of view...

Vivien: I do. In fact, I agree with Ken that they have a point of view whether they really want to or not. Because any good playwright cannot help being taken up with the way the world is going, and I suppose politics come into that. I know nothing about politics and I don’t think I like them at all. But I think that the social conditions in every country are bound to come into any play of any interest. Whether it’s brought in or not, pure propaganda I naturally don’t like because I think it’s always pretty dull. But I think it comes into any play or any movie, whether that movie sets out to put it or not. Because I think any dramatist of any stature naturally deals with the world as he sees it.

Ed: Now, Mr. Goldwyn...

Sam: Yes?

Ed: Didn’t you have a point of view when you decided to do "Porgy and Bess"?

Sam: Yes. I felt that this was, to begin with, the first great American opera that was written. And secondly, I wanted the public to see the negroes as they are.

Ken: I should have said, it simply showed him as he used to be. And I would have thought that, uhm, in spite of your obviously sincere beliefs that politics hasn’t any place in the industry, uhm, I think you will find, and perhaps have found, that a great many people will interpret your film in a social or political terms.

Sam: No.

Ken: You see, it show us negroes as downtrodden, dope fiends, uhm, it’s a very slanted and, uhm, unfair picture of colored activities.

Sam: I beg your pardon. No, I don’t, I, I am sorry. First of all, my story is laid in the period of 19th hundred, then as it was written. Secondly, you might as well say that the public today does not understand Shakespeare or some of the great things that have been written in the past hundred or two hundred years. I, I cannot agree with that at all. I think the idea is to lead them into that period and stick to the period, don’t get out of it. And I think you have a chance to succeed.

Ken: Somebody remarked to me the other day, perhaps a little unjustly, "I see that Uncle Sam is about to give us Uncle Tom”. Now, that may be going a bit too far, but perhaps not a great deal too far.

Sam: Mr. Tynan, it’s the charm, It’s the naïve of the negro in that period that makes this almost a fantasy. But then a fantasy must have a certain sense of reality. And I don’t think politics or anything that you’re talking about have anything to do with that play whatsoever. The idea is to do it better and the screen has a, has greater opportunity than the stage has. And especially when I did this picture in Todd-AO, which has six sound tracks, and Mr. Ira Gershwin sat in the projection room and I showed him some of it in Todd-AO and the remark he made was: "I only wish that George was alive and he could hear this music, his music, played on six tracks now and see...

Vivien: May I interrupt?

Sam: ...the people.

Ed: Yes, Miss Leigh.

Vivien: Please, Mr. Goldwyn has just said something that I don’t agree with at all, because he says that the pictures can do something better. I think they can do it differently, but it doesn’t necessarily mean better. I don’t agree with that at all. They just do it in a different way.

Ed: Well, making a movie out of an opera like "Porgy and Bess” is certainly different. It will be interesting to see whether it’s better.

Sam: People have been afraid in our business to do opera, but I felt It’s a contribution I’d like to make. Because this business has been very good to me and I felt I owe them something, so I spent about 7-8 million dollars, and I have to get back about 16 million to break even, in order to prove that it can be done successfully and it can be better than what the stage has done. And I am hoping that the public will agree with me. And if they don’t agree with me, it will be just too bad, for Goldwyn.

Vivien: Now Sam, are you going to do...

Sam: As a matter of fact, when I produce a picture I don’t usually worry how it’s going to be a box-office success or not. Because the minute anyone starts making a picture and thinks of the box office, they’re 90% a failure before the start.

Ed: This little motion picture, starring Samuel Goldwyn, Vivien Leigh and Kenneth Tynan, will continue immediately after this word from Olin Mathieson. (...) Now, back to Edward R. Murrow and "Small World”.

Ed: Go ahead, Mr. Tynan.

Ken: Are you ever embarrassed, Mr. Goldwyn, when the artistic success of your films is ascribled not to director or the author or the star but to you yourself, who, really, haven’t taken an active, creative role in the picture? I’ve seen a great many films coming out of all kinds of other countries, in Italy, uhm, France, even your own country, Mr. Goldwyn, Poland. And they’re, especially out of your own country, the films nowadays are absolutely, fantastically good! And still, uhm, I don’t think I could name for you who produces any of these films: Italian or French or Polish. Nobody seems to care about that job. Whereas it’s the absolute top, but I think of any other country where, where it is: "Samuel Goldwyn Presents”.

Sam: I agree with you and I know that some very brilliant pictures come out of France, come out of England, come out of Russia. I see most of them. As a matter of fact, I’m seeing one tonight.

Ed: But Sam, Mr. Tynan’s question was: "why is that the producer in this country gets so much more public credit than he does in foreign countries?”.

Sam: My dear fellow, I can only talk about myself at this point. I’ve been at it for 47 years. I started when pictures ran 10 minutes.

Ken: And now they run 10 hours!

Sam: And fortunately, they remember me, that’s all.

Vivien: Four days at the Chinese Theatre!

Sam: People are known by the work they do.

Vivien: We’ve got one pretty good producer in England, who’s been heard of it seems to me, Ken. And his name is Laurence Olivier!

Ken: Oh yes, pretty good director too!

Sam: Vivien, I consider Larry a great producer. I consider him one of the great actors we have in our, in present generation. I have great respect for him. But how many are there? Chaplin was one of them. And you may find one or two more. But how many actors are really producers?

Vivien: Orson Welles.

San: Very good! Orson Welles, unfortunately, has not proven successful in that direction.

Vivien: I disagree with you totally...

Ken: Oh good heavens, Mr. G!

Vivien: I think "The Magnificent Ambersons” and "Citizen Kane" were two finest pictures I’ve ever seen. I saw "The Magnificent Ambersons" again the other day, and it seems to me to be, by far, one of the most wonderful pictures I have ever seen in my life.

Sam: Orson Welles, I happen to like Orson tremendously.

Vivien: Who wouldn’t?

Sam: I think Orson Welles is a very brilliant director.

Vivien: And actor!

Sam: And the one fault I find with Orson Welles, and I have told that so many times, he thinks he’s a writer. He’s not a writer.

Vivien: I think he is!

Sam: And I don’t care how good a producer he is. Or director. He must respect the story!

Vivien: He does everything. I think he’s a wonderful writer. He, after all, wrote "The Magnificent Ambersons", or script of it.

Sam: I never can agree with you on that point at all, because I know him, I watched his career. I know...

Vivien: Well, then we must beg to differ!

Ken: Would you employ Orson Welles, Mr. Goldwyn, as a director?

Sam: Yes, as a director. But not as a writer.

Vivien: But do you agree... but Sam, do you agree that "The Magnificent Ambersons" was a very finely written and directed picture?

Sam: Yes.

Vivien: Because I believe Orson did both.

Sam: Yes, I do, I do, I do.

Vivien: Ah, that’s good.

Sam: But you cannot live on that for twenty years. You see, you, you, no one is perfect. But you must have a better average than Orson Welles has had.

Vivien: I think the peaks that he’s reached are worth a lot of other mediocre peaks that other people have reached.

Ed: Could we change for a moment from Orson Welles to Mr. Goldwyn? I was reading the other day something that was written in 1940 about Mr. Goldwyn, and I’ve noticed it was said: Hollywood is today the motion pictures capital of the world. And the principle reason is that a man named Sam Goldwyn lives here.

Well, today Hollywood is no longer the motion picture capital of the worls as it once was. You’ve all said this. What went wrong?

Sam: I am not defending Hollywood, all of Hollywood’s pictures. But I do say this to you that right now, as we stand today, Hollywood pictures are more popular throughout the world than any other country. The chances are they may beat us unless we improve. And we’re on the way to improving if you look what’s happened the last 2 or 3 years. They’re going in that direction, to make fewer pictures and make better pictures because they found out that the public would just not come and support them.

Ken: Well, I was simply thinking that, uhm, if Hollywood sorts of lost its control of the movie houses, isn’t it because people who came over from Germany and from other parts of the Continent in the under 20s, people like, uhm, Billy Wilder, uhm, Fritz Lang, that kind of person. Now, Hollywood seems to have stopped importing these enormously, uhm, talented people. Could it perhaps be that the talented Germans and Hungarians and Italians nowadays prefer to stay at home, where perhaps they can operate with a little more, uhm...

Vivien: Freedom.

Ken: Yes.

Sam: I don’t know what you mean by freedom. Some people, Laurence Olivier doesn’t need any freedom because he has freedom in his heart.

Vivien: He certainly does and he demands it, old boy!

Sam: He has freedom in his heart...

Vivien: No, you’re wrong there!

Sam: and he knows how to guard his freedom.

Vivien: Sam...

Sam: The thing to do...

Vivien: Sam...

Sam: Yeah?

Vivien: You’ve wrong there. He demands all the freedom in the world and he gets it!

Sam: I see...

Vivien: I’m happy to say!

Sam: I say he’s an exception. Then just a few...

Vivien: Except, of course, that he didn’t get a freedom to do "Macbeth" which was a great shame and a pity and a disgrace.

Sam: Speaking for myself again, I am not yet ready to put, shove under doors 6 or 7 million dollars or 3 million dollars or 2 million dollars and go away fishing.

Vivien: What does that mean?

Ken: Mr. Goldwyn, this talk about shoving 6 million dollars under the door and going, uhm, fishing, I’m not quite clear what you sort of mean by that.

Vivien: I didn’t get that, I’m afraid.

Sam: May I clarify that point? There are two kinds of producers. One is, as Mr. Tynan said, an organizer. And the other really is a producer. I do a great many things myself that others leave to the director. And the chances are, I may be wrong, but nevertheless I’ve been here for 46 years and I’m still working and still doing all right. But I never give the final word to anyone but the Goldwyn. And I shall continue to do that, and when the day comes when I cannot get away with it, I’m going to stop making pictures.

Vivien: That won’t be for a long time, I hope, Sam!

Ken: Mr. Goldwyn, I should have thought, you know, in a way, that sort of overall control by, uhm, one man in some way impeded the liberty of the artist’s concern.

Sam: You can, you might as well say that about Cecil DeMille. No one likes Cecil DeMille’s pictures in Hollywood, but the public or critics, they don’t like it. But the public seems to like them. And after all the public are the, they have the final word, about anyone. So that’s... am I making myself clear now?

Ed: Does that answer your question, Mr. Tynan?

Ken: Oh, yes! But I would be very interested to, to hear Mr. Goldwyn on the other question of: “if anybody will be, uhm, seeing Mr. DeMille’s pictures in, say 50 years time, millions of people are seeing them all over the world now, but I mean will they last as, for instance, "Citizen...

Sam: May I answer?

Ken: Kane" will last?

Sam: May I answer that? He produced a picture of the, uhm, 30 years ago. It was a biblical picture, "The King...

Vivien: "Sign of The Cross", I think.

Sam: "The King of Kings".

Vivien: "Sign of The Cross"!

Sam: No, it was not "The Sign of The Cross".

Ken: "The Ten Commandment"?

Sam: "The King of Kings"! Mr. Tynan, it’s still being shown all over the world.

Ken: Really?

Sam: And his pictures...

Ken: In outlying islands in the South Pacific?

Sam: It is loved by the public...

Vivien: London?

Sam: Some pictures he made were not as good as others. And that applies to every writer, every director, every producer. None of us can hit the 100%.

Vivien: Anybody else’s picture going to live?

Sam: I think "Wuthering Heights” is going to live, as long as I live.

Vivien: So do I!

Sam: And some of "Best Years of Our Lives” or "Gone With The Wind” or any of the outstanding pictures will live. Some of Shakespeare’s plays live.

Vivien: Oh, I think they live, don’t you? They’ve done it for so long.

Ken: Shakespeare’s plays and some of your films and anything else, Mr. Goldwyn? What else will live?

Vivien: Shakespeare’s things live, have lived for a 100 years or more. Great things live. And the bad things die. It’s the same, a man and a woman - when they have bad health they die.

Ed: Our time is up. But I would guess that the movies and the theater will remain healthy, so long as we have producers like Goldwyn, actresses like Vivien Leigh and critics like Ken Tynan.