Watchtower over Tomorrow

1945 U.S. propaganda movie

Review

Near the end of the World War II, the U.S. slowly started assuming that it will be won by the allied forces, and thus new policies and strategies will have to be developed. Following the idea of the League of Nations, now another similar political body started taking shape.

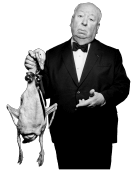

That, of course, transferred to Hollywood - with new policies, new kinds of propaganda movies had to be made. During the WW2, Hitchcock showed a peculiar sense of patriotism - not once did he propose to make this kind of picture, but on the other hand he blindly accepted every offer to take part in making one. Watchtower over Tomorrow was yet another of this type.

Originally, the idea came from State Department and Office of War Information. There was great push (and even greater necessity) for such body to form, and public acceptance was necessary. So even before UN stood on its own administrative legs, people had to cheer for it doing so.

WoW (not World of Warcraft) was a project expected to blatantly glorify UN's creation so people see nothing but positives in it. Alfred Hitchcock and Ben Hecht were two big names recruited and both approached the project enthusiastically.

The U.S. Secretary of State at the time was Edward Stettinius Jr. and he was included in the project to give the content more credibility and make stronger impression. Stettinius only served for 7 months and during that time he rarely appeared in front of camera, so it was a nice exception.

At first, he was not convinced about the idea of appearing in front of camera, and the original plan was for the whole thing to be his speech, with some extra footage added on top. He agreed to star, but in the meantime, probably to his relief, Hecht and Hitch did what was typical for Hitchcock propaganda movies...

Professional ambitions and the desire to challenge themselves took over and they proposed to do more than just film a politician speaking. Why not hire actors and make a more dramatic narration, depicting how the new political construct would function day-to-day and what exactly would be its benefits.

Hitchcock's over-complication in these kinds of circumstances usually worked to his disadvantage, but this time the U.S. government was all ears. The talented pair saw a green light.

Of the two, Hecht probably did more work with early movie preparations. He was allowed to contact various State Department people and torment them with his questions to get information necessary for developing the story. Alfred was expected to coordinate the shooting of this picture, but had developed ideas with Ben too.

Even though both men had laid the foundation of Watchtower over Tomorrow, they went away as soon as they came to the project. Hitchcock had other obligations, which he had to fulfill, while Hecht's reasons seem to be unclear.

But the government must have been very determined to make it happen. Not only did it not give up on it, but after quick changes at the steering wheel, the project was instantly continued.

In place of Alfred, three names came: Elia Kazan (wonderful "A Streetcar Named Desire" screen adaptation), Harold F. Kress (editor who won two Oscars decades later) and John Cromwell (The Prisoner of Zenda, Since You Went Away). Hecht's place was taken by Karl Kamb, a small-time screenwriter.

Four months after the idea of making Watchtower over Tomorrow came to life, the movie was already finished.

While the movie length was not demanding by any standards (15 minutes), it still was a nice achievement, given that the government was involved (which means ideas bouncing around for approvement of all parties), difficult times (during the war, it was normal for propaganda projects to get stuck for years) and two main driving forces behind it catapulted early on.

The picture begins with narration of the Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr., who had been a United Nations advocate before taking the government post. The theme is broad, but revolves around sacrifices, patriotism and the need to act. Near the end, he also praises Hollywood for cooperating with the government in making the necessary propaganda efforts.

The film's purpose was to make the citizenry who gaped at it in the movie theaters fall in love with the wonders of the United Nations. What these wonders were, noone in the State Department seemed to know. I finally put some scraps of information together, larded them with rhetoric and war episodes and sent the script on to Hollywood for production. I came away from a week's toil in the Department stunned by my own naiveté.Ben Hecht

After it, the bomb gets prepared and then shot in a theoretical future scenario. Following this short scene, another monologue takes place. The voice belongs to John Nesbitt, a small-time actor that mostly did short films in the 1940s. Here, he reads a piece that focuses on average families and the need for them to live in peace.

The accompanying film material shows ordinary Americans in positive moods and enjoying living in a peaceful environment. The intention is to echo the sentiment from the monologue, to show those things that need to be guarded at all costs.

Following it is a bus conversation between two average Joes. Grant Mitchell plays an uppity, well-dressed man reading a newspaper, uninterrupted until an obnoxious and a bit arrogant simpleton played by Lionel Stander charges into his personal space.

As more educated, the newspaper owner first explains the article, which praises the United Nations initiative, but then he is challenged for answers and another man steps in. Either an abstract narrator, or a third passenger chips in (we don't actually see him, but the two men look at him) and expands on Stander character's logic while resolving any doubts that the other passenger is having.

This third man is the central character in the picture. He patiently and eloquently describes first steps in forming the United Nations; we learn about International Court of Justice, about various United Nations departments that will regulate local economies, education systems etc.

Finally, a scary fictional scenario is played, in which one of the UN members "doesn't play ball" and decides to prepare the attack on another nation while officially denying to do so. The film presents the theoretical UN reaction to such situation which is intended to discourage the aggressor from going forward with his plan.

Shortly after the midpoint of the movie, we find out what the title stands for. Watchtower over Tomorrow is a hypothetical fantasy-looking enormous building in which representatives of all countries meet, under the United Nations umbrella, and seek solutions to their problems in a peaceful and healthy environment.

After a patronising lecture, both men are fully convinced, but the third man doesn't stop at that and for a short while continues his talk to emphasize the need for action. And on that urging note the picture ends.

Watchtower over Tomorrow is a classic propaganda movie and combines many typical "hooks" of the genre. We have the introduction from an important man in office, a patriotic narrative leading the movie, we see average scenes of everyday life, and the soundtrack is typical too.

It is more a quasi-documentary than it is a story film. Even though there are fictional characters in it, they just serve as a background for what's important, and that is United Nations.

Its history is authentic, various real life political figures can be seen. The concepts discussed exist in a fictional reality, soon to be materialized if UN plans get accepted.

Actors flood the non-existent UN courtrooms and play out the "dealing with a black sheep" scenario, but they only serve to help present proposed UN mechanisms rather than providing an entertaining story by themselves.

In accordance with the unwritten rules of a successful propaganda movie, fictional characters are slightly flat and naive, which is not a problem by itself, but the bus conversation is a bit of a shot in the foot.

The two men clearly represent the higher and lower classes coming together. At first, they have their differences, but they come to an understanding, as they are equally in it whether they want it or not, so they need to put their differences apart.

Unfortunately, while bringing this theme to life, the creators of this picture have unwillingly painted higher class as snobbery that looks down on the lower class, and lower class as obnoxious brutes. Not exactly a pretty picture of things worth defending.

Two of the men involved in this picture had previously worked with Alfred Hitchcock. First one is the already mentioned Ben Hecht.

A true workhorse that did not know how to sit still, he was most active in the 1940s and 1950s, contributing to as much as eight pictures in a single year. It was inside the first of the two mentioned decades that he formed a professional bond with Alfred Hitchcock.

Cinema lovers know his name well through Spellbound and Notorious, but Hecht took part in the making of five other Hitchcock movies as well. These inclusions went largely under the radar until various determined biographers shed light on his involvement, as he went uncredited in all five.

Those movies are: Foreign Correspondent, Lifeboat, The Paradine Case, Rope and Strangers on a Train.

Miles Mander is another person who had worked with Hitchcock, and it's a two decades older partnership. He starred in The Prude's Fall, The Pleasure Garden, Murder and Mary. Of those movies, the first one was directed by Hitchcock's then-superior Graham Cutts, while the remaining three have the Master of Suspense behind the steering wheel.

Dumbarton Oaks is not made up and is an actual location where a United Nations-formulating conference took place. Starting on August 21, 1944, in a private mansion there, Great Britain, China, United States and Russia presented their plan for United Nations structure, ideas and priorities.

After more than two weeks of meetings among the representatives of many gathered nations, agreements have been reached. UN became the real deal following and everyone was hoping that it will be more effective than the previous construct of this type - League of Nations - proved to be.

Like with so many propaganda pictures of the World War II period, here we can also see a unique take on reality that lasted oh so shortly. China and Russia are introduced as allies with which the foundation of permanent peace is to be built.

Shortly after the WW2, Cold War started and all Americans heard since then was that Russians and the Chinese are a threat never to be taken lightly.

Even in 2016 (the time this article is written), this sentiment is strong - in the presidential elections between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump both sides tried to brand the opposition with Russian ties, knowing that it can serve as a powerful deterrent in the public eye.

Because of changes in the political spectrum (Germany in, Russia and China out), even before the war ended, the picture had become outdated. More than that, the government saw the black sheep aggressor theme damaging to the new narrative that they were trying to push.

And hence initial government enthusiasm turned into disapproval. Result? Another propaganda picture in which Alfred Hitchcock was involved that got shelved for decades.

The director's exact role in the making of this film is unknown. It is almost certain that he was only present during the planning phase, and probable that what he and Hecht sketched out served as the foundation on which the film was built.

The fact that Hitch generally avoided talking about his war movies contributed to this being another mystery project. If we haven't found out what he did exactly by now, it is almost guaranteed that we never will.

That didn't damage the picture too much though, as it still is a typical American take on propaganda with few unique twists that sits well in the rich catalog of the WW2 era.

Because of the pure-propaganda direction taken, Watchtower over Tomorrow has little entertainment value and mostly serves as a historical reference for movie buffs and people interested in history, be it war or propaganda. People expecting to find the "Hitchcock footprint" will find nothing but what their imagination will produce.