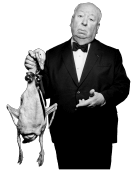

Alfred Hitchcock

Move to America

Summary

United States has always been a magical place for the young Alfred Hitchcock. As a child, he used every opportunity he got to learn about its culture and what it's like to live there.

Even though the actual move there, as you will soon find out, was a prolonged struggle, the fact that he will one day end up a U.S. citizen was always just a matter of time, however long it may take.

Ironically, while Hitch mastered the American ways of making movies, he also stood out because he brought unique British sensibilities to the American audience. What made other early British directors fail to gain traction across the Atlantic Ocean helped him get famous. Not by accident, of course. He knew how to do it.

His roots, Hitchcock never gave up. Until his last days, he felt that his origins are like an invisible wall that separates him from people born and bred in the U.S.A. While he felt lonely because of it, California was where he enjoyed living and work dependencies had little impact on where he chose to spend his adult life. This was his home.

This article tells the story of that change of home, so greatly important to the movie history. It leaves all the mental and stylistic aspects, instead concentrating on the business part, where the struggle was mainly taking place.

U.S. connections

The seed of future affairs to come was planted during the filming of The Passionate Adventure in 1924. One of Hitch's famous early Graham Cutts cooperations saw him doing everything and more to contribute to the picture, despite not being a director yet.

In that film, Alfred worked closely with two women playing central roles: Alice Joyce and Marjorie Daw. Joyce had a brother named Frank, who became a very successful restaurant chain owner, who at some point abandoned his business to join his sister in Hollywood as her accountant. Daw later fell in love and married another entrepreneur - Myron Selznick.

These two connections founded the basis for Hitchcock's hopes of coming to the United States, because it so happened that few years after The Passionate Adventure, Myron Selznick and Frank Joyce formed Joyce-Selznick Agency.

The way their company operated was a revolution in Hollywood. Up to that point, actors were often ruthlessly treated by the studios. Top stars were popular, so they had bargaining power, but outside of this small elite group, they were just workers and studios were their employees. The latter set the rules and actors generally had to adjust.

Joyce-Selznick Agency was innovative, because they brought the third man - an agent - into the equation. Armed with connections, Selznick and Joyce navigated between interested parties and bluffed their way to Valhalla to get their clients good deals. While they got rich, they raised the status of actors in Hollywood from employees to cooperating parties.

Of the two men, Myron was especially good at his craft. Supposedly, his agency plan was motivated with revenge. When he was a boy, Selznick watched his father being brutally treated by the big studios, which drove his production company to bankruptcy.

Having a revolutionary company with familiar faces at the top of its food chain was something that gave Alfred great hope of successfully changing continents.

Alfred's bets were spot on. Soon, Myron Selznick played critical role in making that happen.

First approaches

Joyce-Selznick Agency became a hit in a heartbeat, drawing many top stars, motivated by the perspective of getting fatter paychecks. They dominated Hollywood so fast that soon Joyce and Selznick opened an office in London (ran by Harry Ham).

When Hitchcock was temporarily out of work, Myron sensed an opportunity and through that office contacted the director, hoping that he might sign another with their help.

Selznick wasn't the only one interested though. Sam Goldwyn (Goldwyn Pictures, Paramount, MGM) and Carl Laemmle (Universal boss) knew that there probably is money to be made on the chubby director and made preliminary contact to set the table for potential future negotiations.

Of the two, Alfred leaned towards the first one, but Laemmle was not giving up and pursued him aggressively. Seeing the interest, he decided play hard to get and demanded $2,500 per week for 20 weeks and guaranteed two American films. The first one could be chosen by the studio (which Hitch found hard to swallow), but the second had to be his.

Even though this was a time in Hitchcock's career when the director was failing to secure the films he wanted on the terms he wanted, and his bank account balance was nothing to brag about, he knew better than to sell himself cheap.

Unfortunately, this approach wasn't helping him. The big producers cared about money and money only and Hitchcock was simply not worth what he was asking from them.

The problem wasn't that they didn't believe that Hitch doesn't have it in him to make movies that can gather masses in theaters, but they needed Americans to do so. And the U.S. market was stubborn - no British movies! Dozens of very promising directors before Hitch, each seemingly the one to finally break the ice, failed to do so.

Hitchcock was a wild bet - why would he be an exception to the rule? And on top of that, he started expecting what was close to what they pay for 'sure things'.

David O. Selznick enters the picture

Despite many interested parties, nobody was willing to go the full way and Hitchcock was getting anxious. He continued to work, keeping his fingers crossed, but wondered if he's ever going to make his dream a reality.

In 1935, shortly after The Man Who Knew too Little was released, Hitch contacted Harry Ham and asked him to open negotiation channels again. This time, Michael Balcon found out about it and got very angry, demanding those channels stay closed. Balcon was the head of Gaumont Pictures at the time, to whom Hitchcock was signed. The director was one of the studio's most prized possessions and Balcon indeed was very possessive of him. (after Hitchcock migrated, Balcon stayed resentful for more than a decade)

Two years later, Michael switched studios to MGM, who were also expanding to the British market. Seeing great value in Hitch, he offered him contract with his new employer, accenting that it could include an occasional American movie. The great director saw that as a compromise he is not willing to make, and declined.

Another man related to MGM was Myron's brother David O. Selznick (also simply known as DOS). This man though he was on his way out of MGM at the time, setting up his own agency. A would-be competition to his brother's business, but in reality his associate in many cases. He didn't know Hitch personally like Myron did, but more than made up for it with his enthusiasm.

David not only did not lag behind his brother business-wise, but he was an even bigger visionary. In the late 1930s, he was just warming up while Myron was already at full speed, but soon he would become the most powerful man in early Hollywood history (until another man named Lew Wasserman came and raised the bar to the level unbeaten to this day).

Hitchcock quickly became enthusiastic about the less-known Selznick, but intended to keep his cool. Both sides were aware that due to not being a citizen of the United States, Hitch will have to pay extra taxes, which will eat considerable part of his earnings, so an offer has to be high enough to compensate for that. This was a problem. Another one was that Alfred wanted multi-picture deal, which made the financial liability even bigger.

When the movie Young and Innocent was completed, Hitchcock, his wife Alma, their daughter Pat and the director's assistant Joan Harrison travelled to the United States. Finally, he could experience all the sightseeing destinations that fascinated him for so long first-hand.

It was a quality family time, but the main reason for the trip was business. Selznick Agency set him up with a number of talks and semi-negotiations with clients who may be interested in hiring him.

It was also a chance to meet David O. Selznick face to face. Hitch was hoping that they can strike a deal on the spot, but came away from the meeting unsatisfied. Selznick insisted on signing a deal with the MGM-British Studios, a much safer variant for the agent.

The deal gets stuck

Neither side was willing to compromise, so negotiations halted for close to a year. Then, Selznick made contact and offered Hitchcock to direct Titanic under a one-film contract. The story repeated itself once more - Hitch politely declined. (Hollywood had to wait 19 more years for that movie to see the light of day)

Concluding that he needs to fight for it more, he again traveled to the United States (this time with his wife only) and engaged in more negotiations.

Confrontations with David O. Selznick were again disappointing. On top of his previous fears, he was now unsure whether Titanic should be the project he should set Hitch up with.

The second day of talks finally brought some good news: Sam Goldwyn assured the director that he is willing to give him a movie called Scotland Yard as part of a double deal with Selznick. But again, it was a mixed bag: Goldwyn was afraid to strike a deal prematurely, relying on Selznick for the final say, and Selznick had already made his intentions clear.

The agent was keeping the channels alive while continuing to apply pressure, so he doesn't make an overblown deal with Hitch. After hitting the wall in the U.S. for the second time, he might have thought that that this is the moment when the talented Brit finally lowers his expectations. Surprisingly, it was the other way around.

Because of the extra taxes, the $50,000-per-picture deal that was on the table from the start now looked like a poor man's salary. Realizing that he would actually be making less money in America than in Great Britain, he upped his requirements to $75,000.

In the background of this story, another drama was unfolding. Back in England, the chubby prodigy was responsible for the screen adaptation of Daphne du Maurier's phenomenal novel Jamaica Inn, starring the legendary Charles Laughton.

Because Hitch's mind was on another continent, the bar was set high by the novel, the film was trapped by many problems and even the subject matter was not very Hitchcockian (the director and costume movies didn't go along very well), it ended up buried alive by the critics and the audience found it average. It was the less important matter for the Brit anyway.

Seeing all the dramaturgy of those unfortunate negotiations, Myron decided to step in and mediate between the two parties. Alfred managed to turn him into his ally and convinced the businessman to go to David and demand that he presents the final terms. No more waiting, it's now or never.

Selznick was ok with making a final stance, but he wasn't budging by a millimeter and offered a one-movie contract for Titanic (or other production specified by David) with the optional extension of agency patronage for up to four years. In other words, if the first U.S. Hitchcock film would be a success, they would gladly find him two or three more and take a cut, or hire him themselves. If not, he is on his own.

Back with the terms, Myron now turned to his brother's ally. He aggressively pushed for Alfred to sign the deal, convincing him that even though it's not what he expected, it's just a start and he won't get better terms anywhere else. Finally, Hitchcock gave up to these final terms. David O. Selznick won.

Breaking point

This wasn't the end of problems for the young Englishman. The negotiations were in the midst of a storm that was the filming of Gone with the Wind, a movie that would soon become one of the most iconic pictures ever created. As big as Hitch was physically, he was still a small fry to David, who was producing the film (and there were plenty of issues to keep his nights sleepless).

When Hitch struck a deal, the picture was still in the making and all the producer's efforts came into finalizing it. On the side and more anxious as time passed was Alfred, knocking on the big door. There was no sign of Titanic, or any other project coming his way. When he was confronting DOS about it, he was just brushed off.

Funnily enough, the producer was like a Pavlov's dog. Cold as he was towards the director in that period, when somebody else approached him with an offer, Selznick was barking seconds later to protect his commodity!

He wasn't the only powerful man in Hollywood and the interest in the Englishman was growing the longer he was inactive (and therefore, in the eyes of many, available).

The big success of his latest movie The Lady Vanishes only added to that. For the first time, American audience caught up with his creation before he managed to make one on the U.S. soil. The prestigious New York Film Critics organization gave him an award for best director.

Passive as Selznick was at the time, he must have felt reassured when he found out about the distinction. His constant worry about Hitch was if the American audience will like his kind of films, his techniques, his specific sense of humor, or if they will just say it's weird, quirky and overly British. Now, his worries started to fade away.

Final deal

Feeling increasingly confident in his client's abilities and increasingly more scared of losing him, David knew that he has to act. Thus was born a new contract, much more beneficial to the director. Now, he was obliged to make two movies per year, one for Selznick International Pictures and the other either for SIP, or other studio if both Selznick and Hitchcock agree on it.

Another important change for the director was that he was now on a monthly payroll, instead of making money per pictures done. Instead of spending his money and wondering when and if he will finally get a source of income, Selznick was now the victim of his inactivity while Alfred was collecting major paychecks for slacking off.

On April 10, 1939, Hitchcock checked in at the Selznick headquarters and into his lot, his very first U.S. office.

Ironically, the director's first American movie was another adaptation of Daphne du Maurier's novel. After the Jamaica Inn fiasco, it seemed like a risky move on paper, but Rebecca proved to be an astonishing work of art, with the end so worth the watch for people who read the book.

Fans instantly fell in love with the director, and press did so too, with the chubby man proving to be surprisingly funny and charismatic in front of camera.

Even though by that point he had already done many fantastic movies, the most fruitful period of his career was just beginning.